17 Dec. 1758–29 June 1837

Macon took to the field with the New Jersey militia in 1776. When his college closed, he returned home to Warren County to read law (which he never practiced) and English history. The interruption in his military service was not unusual since the Revolutionary War was fought by fits and starts and gentlemen served at will. (A similar hiatus occurred in the service of James Monroe and John Marshall.) Macon reentered the army in 1780 in a company raised and commanded by his brother. Typically, he refused a commission and the enlistment bounty. He was probably present with the American forces during the disastrous Camden campaign. In 1781, as a twenty-year-old private encamped on the Yadkin River, Macon received word of his election to the North Carolina Senate, which he reluctantly entered and to which he was reelected until 1786. He was immediately recognized as a leading member.

After the Revolution, Macon served for a time in the House of Commons and was identified with Willie Jones and the predominant anti-Federalist sentiment in North Carolina. He declined to serve in the Continental Congress in 1786, and his brother John voted against the federal Constitution in both North Carolina ratifying conventions. However, Macon accepted election to the federal House of Representatives and entered the Second Congress in 1791. He served in the House for the next twenty-four years, then took a seat in the Senate, where he remained for thirteen years, thus representing North Carolina in Congress from age thirty-three until his voluntary retirement at seventy.

In the House from 1791 to 1815, he was Speaker (1801–7), a candidate for Speaker (1799 and 1809), and chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee (1809–10). In the Senate from 1815 to 1828, he was chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee (1818–26) and president pro tempore (1826–28). In both houses he served on the main financial committees and was chairman of numerous select committees. During his congressional service he declined cabinet appointments at least twice, and he served long periods as a trustee of The University of North Carolina and as a militia officer and justice of the peace in Warren County. For the first third of the nineteenth century he was the dominant personality of the predominant Democratic-Republican party and the most respected citizen of North Carolina both within and outside the state.

It was Macon's pride that he never campaigned for an office or asked any man for a vote. His legislative and political skills were neither rhetorical nor managerial. His strength and influence lay in personal force, exemplary integrity, shrewdness, a contented (or static) public, and undeviating adherence to fundamental principles. These principles, forged in the Revolution, did not change in a political career of half a century. They included individual freedom, strict economy and accountability in government expenditures, frequent elections, limited discretion in officials, avoidance of debt and paper money, and Republican simplicity in forms. Macon was the purest possible example of one type of "Republican" produced by the American Revolution. He was satisfied with a society of landowners who managed their own affairs and wanted neither benefits nor burdens from government. He wanted a government conducted with honesty, simplicity, and the maximum liberty for the individual, community, and state. He believed that North Carolina approached this ideal, and he fought a losing battle to hold the federal government to it. To Macon, the success of a democracy depended not on the progressiveness and vision of leaders but on the willing consent of the people. Because he opposed most appropriations and innovations, even when he stood nearly alone, he has often been described as a "negative radical." True to the spirit of "esse quam videri," Macon practiced what he preached. He was in his seat faithfully when public business was being conducted, drew from the Treasury only his actual travel expenses rather than the maximum allowance (as was the practice), and lived simply in Washington, often sharing a bed with a visiting constituent.

Ideological purity did not detract from Macon's political shrewdness (he advised Jefferson against the abortive Chase impeachment, for instance,) or prevent him from being chivalric towards opponents in personal relations. Despite his firmness, Macon was often pragmatic in matters of political tactics and knew when to compromise and yield to his party on smaller issues. His judgment was always well balanced, his dealings moderate. His speeches were businesslike and to the point, his first congressional speech reportedly being one sentence. With one pithy question in debate, he burst many grand congressional bubbles. "Be not led astray by grand notions or magnificent opinions," Macon told a young follower. "Remember you belong to a meek state and just people, who want nothing but to enjoy the fruits of their labor honestly and to lay out their profits in their own way." With this philosophy he dominated the state for decades. In only one brief period (1801–5) was he a dispenser of federal patronage, and then he refused to use it politically.

Macon's political career had three phases: Jeffersonian Republican leader, 1791–1807; "Tertium Quid," 1807–ca. 1815; and elder statesman thereafter. When he entered the House of Representatives in 1791, he was immediately identified with the group opposed to the emerging Federalists and took a leading role in the parliamentary battles of the 1790s in which the Jeffersonian coalition was forged. These services led to the speakership, a post that, Macon said, he entered without seeking and left without regret. Losing the chair in a disagreement with the administration wing of the party, which he felt had compromised with Federalist principles and had used rather than eliminated the federal patronage, he was thereafter identified with the "Old Republican" group. He opposed taxes, the protective tariff, internal improvements (at federal expense), all expenditures not necessary to the honest fulfillment of the most essential functions of the government, a national bank, executive patronage and discretion, and any compromise with northern antislavery agitation. The principles that John Taylor expounded and John Randolph dramatized, Macon personified. Remaining independent, never attending the party caucus, and opposing the election of both James Madison and James Monroe, he supported the incumbent administration when he could and never engaged in opposition for opposition's sake. He reluctantly voted for the Embargo. During the War of 1812 he was willing to raise and support troops but opposed a navy, national conscription, and executive discretion.

By the time he entered the Senate in 1815, Macon was already a venerable figure, a stature that increased as survivors of the Revolution and exponents of pure Republican principles became rarer. Although he was evidently displeased with the increasingly dynamic politics of the postwar period and felt that true Republican virtue was being lost, Macon undoubtedly had a considerable impact on the next generation as a prophet of both "Jacksonian democracy" and southern separatism. Towns and counties across the South were named for him. He was widely discussed for the vice-presidency in 1824 and received the electoral votes of Virginia for that office. In 1828 he was wooed unsuccessfully by John Quincy Adams as a running mate. He was lukewarm to Andrew Jackson but gave the Jacksonian coalition his support as a lesser evil from 1828, and he served as a Van Buren elector in 1836. He evidently regarded the emergent Democratic party as the nearest available approach to a coalition of southern planters and northern republicans against antislavery agitation and economic exploitation. Opposing nullification and considering secession the proper remedy, he also chastised Jackson for his responding proclamation, which he found to be as contrary "to what was the Constitution" as nullification. In 1835 Macon was unanimously elected presiding officer of the state constitutional convention, although in the end he opposed the revisions that were adopted, especially the change from annual to biennial elections.

Macon is said to have destroyed his own accumulated papers, probably out of the same "republican" distaste for pomp and idolatry that led him to oppose expenditures for a tomb for George Washington and to forbid the erection of a monument over his own grave at Buck Spring. This fact has discouraged biographers, although a large number of Macon's letters survive in scattered depositories and publications. He has figured in many articles, addresses, and theses concerning him specifically or Jeffersonian and Jacksonian politics. William E. Dodd's Life of Nathaniel Macon (1903) could be amplified and corrected in many details but remains a substantially accurate and usable work. Perhaps more valuable and practicable than a new biography would be a reliable and complete edition of Macon's speeches and letters, a project that probably could be encompassed in one volume.

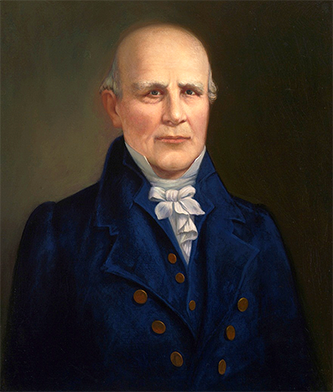

Likenesses of Macon are rare. Neither the state nor The University of North Carolina owns a portrait. The massive American Library Association index to nineteenth-century engravings does not even contain an entry for Macon. Perhaps the most readily available likeness is the unidentified portrait published in William Henry Smith's Speakers of the House of Representatives. . . (1928).

At any rate, Macon's republicanism was one of deliberate choice, not of inertia. As William E. Dodd commented with a sense of marvel, "He actually believed in democracy," in allowing the people to govern themselves. He was of a generation, class, and region that "knew the difference between the demands of popular institutions and special interests" and that deliberately chose a limited government as the accurate reflection of its social fabric. Certainly it would seem that the "spirit of Macon" was long the spirit of North Carolina, a spirit that, however foreign to the modern temper, lies at the heart of the origins of American democracy. Perhaps no one ever served the state more unselfishly or better displayed its traditional modest virtues.