20 May 1768–12 July 1849

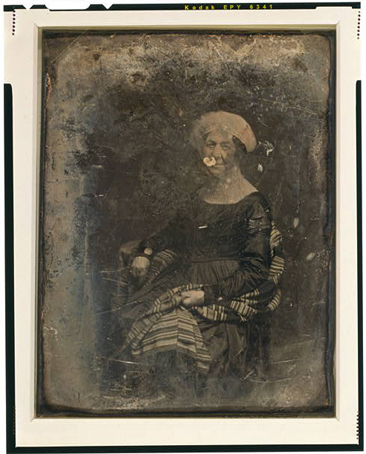

Dolley Payne Todd Madison, First Lady, social arbiter, and heroine of the War of 1812, was born in the New Garden settlement of Rowan County (now Guilford College in the bounds of Greensboro). Her Quaker parents, merchant John Payne and his wife Mary Coles, had moved there from Hanover County, Va., in 1765. In keeping with Quaker custom, her name was entered in the records of the New Garden Monthly Meeting under her parents' names: "Dolley their daughter was born ye 20 of ye 5 mo 1768." All of her life, when writing her name, she always spelled it Dolley.

When Dolley was just eleven months old, her family returned to Hanover County, where she spent her childhood and attended an old-field school and later a Quaker school in the local Cedar Creek meetinghouse to which the Paynes belonged. Opposed to slavery, John Payne in 1782 freed his slaves and the following year moved his family to Philadelphia, the national capital. Here Dolley was witness to governmental as well as social activities. She married a promising young Quaker lawyer, John Todd, Jr., and they became the parents of two sons, John Payne (1792) and William Temple (1793). In the summer of 1793 a yellow fever epidemic struck the city, and both Dolley's husband and her younger son fell victim on the same day.

With her first son, John Payne, she continued to live in the house that she and her husband had bought in 1791. She had many admirers, among whom was Congressman James Madison, of Virginia, often referred to as "The Father of the United States Constitution." She met Madison in May 1794 and they were married in September. Her public life began in 1801, when President Thomas Jefferson named Madison secretary of state. Since both the president and the vice-president, Aaron Burr, were widowers, Mrs. Madison became Jefferson's acting hostess and she soon set high standards for the social life of the new national capital, Washington, D.C. She opened her own new home to congressmen, to representatives from other countries, and even to visitors to the city. At these gatherings topics of wide-ranging importance were discussed, and occasionally Dolley was criticized for her role in some of them. Nevertheless, she received guests without regard to party politics and attempted to make everyone feel welcome. One of her friends, Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith, in her later biography of Dolley Madison, stated: "The kindly feelings thus cultivated, triumphed over animosity of party spirit, and won a popularity for her husband, which his lofty reserve and old manners would have failed in ineffecting."

She presided at the president's house on 4 July 1803 at a great reception announcing the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson and the Madisons were congenial, and during Jefferson's administrations she was his hostess when ladies were invited or when he needed advice concerning his family. It was observed that Jefferson loved Madison as if he were a son, and he endorsed the secretary of state as his successor as chief executive.

In 1809, when Madison was inaugurated as the fourth president of the United States, his wife became First Lady in name as well as deed. Although she did not dance, she approved of closing the inaugural celebrations with a grand ball. By that time she was so popular that she was almost pressed to death by those seeking a close glimpse of her. Mrs. Smith wrote: "It would be absolutely impossible for anyone to behave with more perfect propriety than she did. Unassuming, dignity, sweetness, grace."

The presidential mansion had never been adequately furnished; Thomas Jefferson had used furnishings from his own home during his two terms in office. Before Madison's inauguration, however, a congressional grant of five thousand dollars had been made for the decoration of the interior of the house, and it was Dolley who undertook the assignment. With the assistance of architect Benjamin Latrobe, the president's home was decorated and furnished in a highly acceptable manner. It won consistent praise. Mrs. Madison conducted weekly dinners for thirty invited guests, and on a regular basis the drawing rooms were opened to the public. She often was present to greet casual visitors and to discuss the progress and development of the country; she frequently shared with President Madison her sense of the concerns of the people.

Dolley Madison is credited with softening some of the verbal attacks leveled against her husband, particularly with reference to the War of 1812; even in the face of national divisions, he was reelected to a second term. In spite of the war, she continued her weekly dinners and drawing-room receptions, which provided her an opportunity to gain an understanding of the issues confronting the nation as well as to give heart to the people away from Washington. She also served refreshments to passing groups of soldiers, wrote letters to family and friends, and pledged herself to do everything she could for the good of the country.

When it was known that the British had landed along the Chesapeake and were headed towards Washington, she packed the Cabinet papers and other valuable records for transport, directed that Gilbert Stuart's portrait of George Washington be removed from its heavy frame and taken to safety, and loaded conveyances with various items of value and sent them off for safekeeping. A letter that she hastily wrote to her sister, Mrs. Lucy Washington, is perhaps the most valuable surviving source concerning the British capture and burning of Washington. The presidential mansion was gutted, and afterwards the blackened walls were painted white to help conceal the damage; it was henceforth known as the White House.

At their home, Montpelier, in Virginia, Mrs. Madison worked on her husband's papers and entertained a constant flow of visitors from at home and abroad. After Madison's death in 1836, she returned to Washington, where she was almost as popular as she had been as First Lady. She was invited to be at the forefront of all important occasions. Nevertheless, she faced difficult financial responsibilities. The Madison estate in Virginia was sold, as were some of Madison's papers; she mortgaged her home in Washington and even was reduced to borrowing from understanding friends. Relief came on her eightieth birthday when Congress purchased the remainder of Madison's papers and placed them in the Library of Congress.

On one occasion Henry Clay remarked to her, "Everybody loves Mrs. Madison." She instantly replied, "That's because Mrs. Madison loves everybody." She promoted music, drama, art, the Library of Congress, an orphan's asylum, inventions, sports, the George Washington Monument, and—according to legend—the writing of "The Star Spangled Banner," as well as keeping the nation's capital in Washington after the War of 1812.

Dolley Madison knew personally the first eleven presidents of the United States. In February 1849, as a special guest at the President's Ball, she strolled through the White House with another North Carolina native, President James K. Polk. In July of that year she died at age eighty-one and was buried in the Madison family cemetery at Montpelier.