Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Roots of Civil Rights Activism in North Carolina; Part iii: Brown v. Board of Education and White Resistance to School Desegregation; Part iv: Integration Efforts in the Workplace, Sit-Ins, and Other Nonviolent Protests; Part v: Forced School Desegregation and the Rise of the Black Power Movement; Part vi: Continued Civil Rights Battles in the State

Although emancipation formally ended slavery and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments guaranteed the rights of citizenship to African Americans, in everyday life segregation continued to have an impact on whites, blacks, and Native Americans in North Carolina after the Civil War. During the Reconstruction era blacks took advantage of their newfound freedoms to found schools and colleges, begin businesses, and create a variety of social and political organizations. Formal political representation came as blacks were elected to offices at the state and federal levels, particularly from the Black Belt region in the northeastern part of the state, where newly freed slaves joined significant numbers of freeborn blacks to establish a powerful political and social force.

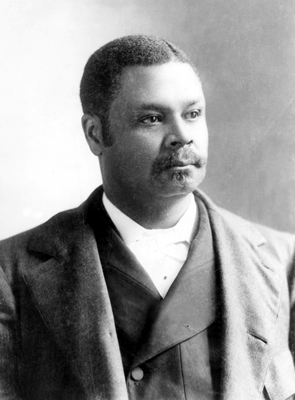

Practically all of the political advances made by black North Carolinians began to erode, however, with the end of Reconstruction and were rolled back altogether in the state's white supremacy campaigns of 1898 and 1900. After Democrats in the General Assembly crafted new voting restrictions that disfranchised black voters in 1899, the state's last remaining black congressman, Bladen County native George Henry White, recognizing the inevitability of his defeat, decided not to run in the 1900 election. For decades after that, African Americans struggled to regain what they had lost, to end segregation, and to enjoy the full rights and freedoms of citizenship on an equal footing with whites.

Black North Carolinians began working to recover their civil rights almost immediately after they were taken away at the opening of the twentieth century. Individuals and groups worked most often on the community level to effect change. The state's first chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were established in 1917, and their members advocated antilynching legislation, fair employment practices, equal educational funding and access, and voting rights. Black churches and schools were also important early incubators for civil rights activism. In 1932 a group of black ministers gained notoriety by protesting at the dedication of Raleigh's new War Memorial Auditorium because they were required to sit in the balcony. During the 1930s, student groups in Greensboro and elsewhere in the state initiated boycotts of theaters for similar restrictions on seating for blacks and for their failure to show racially balanced movies. These early boycotts laid the groundwork for similar tactics used later to protest segregation in department stores and other commercial establishments.

In the 1940s the statewide movement for civil rights gained new momentum, particularly as black veterans returned home from World War II in the second half of the decade, declaring that their service to the nation had earned them an equal voice in politics and other walks of life. The NAACP grew significantly in the state during this time, and local activists who had come of age in the 1920s and 1930s took on new leadership positions in the national civil rights movement. Among these leaders was Ella Baker, a native of Virginia who was raised in Littleton and attended Raleigh's Shaw University before becoming national branch director for the NAACP. In 1943 Baker persuaded the state's branch presidents to form the North Carolina Conference of Branches and helped revitalize several of the state's local civil rights organizations.

In addition to the NAACP, other civil rights groups emerged and developed tactics in the 1940s that contributed to later successes of the movement. During this period, union activists in Winston-Salem linked concerns for the civil rights of black tobacco industry workers with their push for workers' rights at R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. Elsewhere in the state, similar alliances were formed between labor and civil rights activists, with both communities pushing for improved working conditions and equal pay. Meanwhile, in 1947, eight white men and eight black men began a bus pilgrimage through the South to test the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), another key civil rights organization, organized the "Journey of Reconciliation," whose members were arrested several times, including in North Carolina. A precursor of the Freedom Rides of the 1960s, the Journey of Reconciliation was an early example of the "direct action" strategy CORE and other civil rights groups employed from the 1950s to the late 1960s.

Individuals such as E. V. Wilkins also effected change in their communities. In 1952, after a long struggle led by Wilkins and his sister, Wilie Mae Winfield, black citizens in the Washington County community of Roper successfully overturned the community's "literacy" test (which amounted to an arbitrary evaluation of penmanship) and regained the right to vote. Such local gains mirrored and in many cases anticipated national developments.