Classification

Class: Aves

Order: Anseriformes

Average Size

Length: 19.8 -27.5 in.

Wing: 10.4-11.4 in.

Weight: females 2.5 lbs., males: 2.75 lbs.

Food

Omnivorous and opportunistic feeder; consumes insects and aquatic invertebrates, acorns, seeds, tubers and vegetative parts of aquatic plants, and crops, such as corn, soybeans, rice, barley, and wheat.

Breeding

Birds become sexually mature between 5 and 9 months. Mating occurs during spring. Average clutch size of about 8 or 9 eggs, with one egg laid per day.

Young

Normally, a hen will have only one clutch; however, a second clutch is possible with an early first clutch. The incubation period is 28 days. After incubation, the hen tends her brood for 8 weeks; by then, the brood can attain flight.

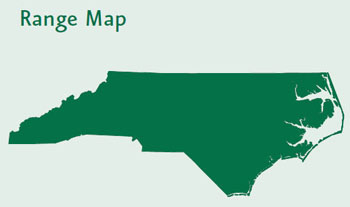

Range and Distribution

The mallard breeds across much of North America and is found in every state during specific times of the year. It is found over the entire state of North Carolina. The home range for paired mallards often exceeds 700 acres. Factors that influence the mallard’s range or alter its patterns include human interference, habitat and food abundance, and/or lack of a mate. Mallards have been recorded flying at speeds of 70 mph. They typically cruise at air speeds of 30 mph.

General Information

The mallard is the most abundant and commonly recognized species of duck in North America. The male’s characteristic and conspicuous green head, grey flanks, and black tail-curl make it the most easily identified duck. An American clothing manufacturer uses a mallard head for its logo, as does Ducks Unlimited, a conservation organization dedicated to restoring waterfowl and wetlands.

The mallard has long been a highly prized game bird and source of meat in North America. It is the source of all domestic ducks except the Muscovy. Feral populations of tame ducks, composed of a mixture of wild mallards and domesticated birds, live in urban areas throughout the world and habituate to people who feed them.

Description

The mallard is a large, dabbling duck with broad wings. The male’s (drake) distinctive green head and brown chest are separated by a white neck-ring, contrasted by gray sides, a brown back, and a black rump. The female (hen) is marked in a mottled pattern of light and dark brown streaks, accented by a dark brown streak through the eye. Both male and female mallards sport a violet-blue spectrum on each wing. Mallards possess excellent eyesight and hearing, giving the duck an advantage when an intruder nears. The mallard is more vocal than all other ducks and uses a variety of quacks to indicate its actions and moods.

History and Status

The mallard’s success in the wild is due to its adaptability to different habitats, including an ability to tolerate cold climates, a variety of food, and tolerance of human activities. The mallard’s population status is often an indicator of the health of all waterfowl. Biologists monitor mallards when establishing hunting regulations for most species of ducks in North America. Although the mallard is the most heavily hunted duck in North America, its populations are considered stable. In 2007, mallard abundance was estimated at 8.5 million birds. Mallard numbers, along with many other species of ducks, declined dramatically in the 1980s after an extended drought in the Prairie Pothole Region. The prairie potholes are an expansive area of wetlands, located in the north-central United

States and southern Canadian provinces that produce more waterfowl than any other region in North America. During the 1980s drought, loss of breeding habitat occurred as wetlands disappeared and prairie potholes were drained to make way for more farming land. Most ducks, including mallards, rebounded as water returned to the prairies in the 1990s and widespread conservation measures were enacted to protect breeding habitats in the Prairie Pothole Region.

Habitat and Habits

The mallard duck is the most adaptable of all ducks and is well dispersed throughout North America. While most mallards breed on the northern prairies, many nest elsewhere, including North Carolina. Although the mallard prefers shallow wetlands for feeding and resting, it builds its nest on dry ground. During the winter months, an abundant supply of food and a safe roosting site are adequate needs for survival. Mallards feed primarily on natural foods such as wild rice, pond weed, smartweed, bulrushes, and a number of other emergent and submerged plants. When natural foods are limited or not available, mallards rely on grains such as corn, soybeans and wheat that are left in agricultural fields as the result of harvesting, or left standing to provide winter food for waterfowl. In many agricultural areas of Canada, grain crops such as wheat have been heavily damaged because of large, migrating flocks that invade the fields after cutting and prior to combining. In the southern states, flocks of mallards often feed in rice fields. The majority of the mallard population is migratory. This means they leave their nesting sites in the North and fly as far south as northern Mexico, beginning in the fall.

People Interactions

Mallards, like many forms of wildlife, are shy and would rather be left undisturbed. The mallard can be legally hunted in Canada, the United States and Mexico. In the southern United States, including North Carolina, the practice of releasing captive-reared mallards for hunting purposes has grown and is cause for concern. This practice increases the potential for spreading viral diseases to other waterfowl, as well as competition and hybridization with black ducks, a declining species. It also has the potential to influence population surveys of wild mallards.

NCWRC Interaction: How You Can

Help

Mallards are a common sight when visiting parks, ponds, or any areas where water may be present. Many are likely domestic in origin, are feral (meaning they were originally domestic mallards but have become established in the wild) or are hybrids resulting from interbreeding of wild and domestic mallards. During the winter, they could be migratory mallards originating from breeding areas far north of North Carolina. Regardless of their origin, mallards become habituated to areas where they are fed by humans.

Feeding ducks may seem like fun and a way of helping wildlife cope with living in the wild, but feeding waterfowl can actually be harmful to humans and ducks alike. When people provide handouts, large numbers of ducks gather in one place and diseases can be spread.