by R. P. Stephen Davis Jr., 2006; Additional research provided by Ansley H. Wegner; Revised December 2021

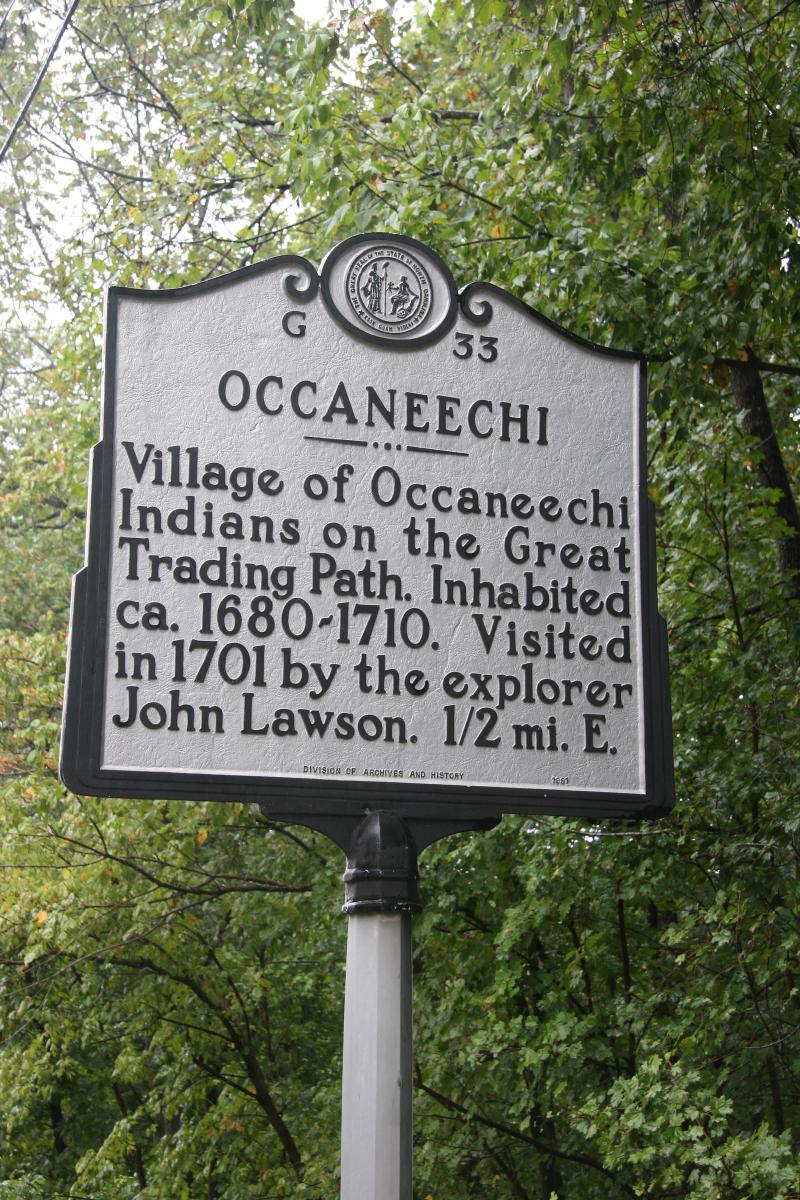

John Lederer, a German explorer and doctor, visited and described the tribe's island village in 1670. A subsequent visit by James Needham and Gabriel Arthur in 1673 was described in a letter written by the Virginia trader Abraham Wood. The Occaneechi's control of the trade resulted in part from their strategic location astride the Great Trading Path that led from the Virginia Colony to the Catawba and Cherokee. This situation came to an end in 1676, when the Occaneechi were attacked by a frontier militia led by Nathaniel Bacon. Following their defeat, the Occaneechi abandoned their island home on the Roanoke and moved south to the Eno River at present-day Hillsborough in Orange County. English explorer John Lawson visited and briefly described their village there in 1701. He noted that "their Cabins were hung with a good sort of Tapestry, as fat Bear, and Barbakued or dried Venison; no Indians having greater Plenty of Provisions than these."

Lawson's "Achonechy" Town was excavated by archaeologists from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill between 1983 and 1986. These excavations revealed a small, briefly inhabited village that consisted of about a dozen wigwamlike houses that formed a circle surrounding an open plaza. At the center of the village was a large sweat lodge. The houses were surrounded by a defensive stockade, and a cemetery containing numerous graves was located just outside the village. Artifacts found at the site included fragments of Occaneechi-made clay pots and stone tools and numerous European-made items acquired through trade, such as axes, hoes, knives, scissors, bottles, and glass beads. Food refuse, consisting of animal bones and charred plant remains, reflects a subsistence economy based primarily on growing corn, beans, and squash and hunting deer. Relative to the small size of the village and the brief time it was occupied, a large number of graves were found, attesting to the devastating impact that Iroquois war parties and European-introduced diseases had on the Occaneechi in the early eighteenth century.

By 1712 the Occaneechi had left the Eno River Valley and moved to the northeast, seeking the protection of the Virginia colonial government at Fort Christanna on the Meherrin River. There they joined the Saponi, Tutelo, Stenkenock, and Meipontsky, gradually losing their identity as a distinct tribe. They are last mentioned in the historical record in 1728 by William Byrd II, who observed that the Fort Christanna Indians were "now made up of the remnant of several other nations, of which the most considerable are the Saponis, the Occaneechis, and Stoukenhocks, who, not finding themselves separately numerous enough for their defense, have agreed to unite into one body, and all of them now go under the name of the Saponis." Although circumstantial evidence suggests that at least some of the remaining Occaneechi may have migrated northward with the Tutelo and Saponi to Pennsylvania and New York, a small community of Indians in North Carolina's Orange and Alamance Counties, known as the Occaneechi Band of Saponi Nation, claim descent from the eighteenth-century Occaneechi and were officially recognized by the state of North Carolina in 2001.

The Ocanneechi Band of the Saponi Nation is governed by a nine-member council.

In August 2002, the Ocanneechi Band of the Saponi Nation launched the Occaneechi Homeland Preservation Project. The project included plans to purchase lands in the “Little Texas” community of northeast Alamance County. The tribe owns land to be used for economic development for the tribal community and for tribal administrative offices. The tribe worked with the Landscape Architecture Department at North Carolina A. & T. State University and the Rural Initiative Project of Winston-Salem to create a master plan for the site, which includes a permanent ceremonial ground, orchards with heirloom apples, chestnuts, paw-paws and muscadine grapes, a reconstructed 1701 Occaneechi village and 1880’s era farm, educational nature trails, a tribal museum, administrative office space, and meeting and classroom areas. Elementary and middle school students regularly visit the tribal center property and learn about traditional dance, lifeways, outdoor cooking, storytelling, flint-knapping, hunting and fishing, and Southeastern regalia.