Although farm educators championed increased poultry production as a new source of income, poultry raising remained underdeveloped, in part because it carried the stigma of being "women's work." Compared to other regions of the country, poultry production in the South lagged far behind. In 1900, for example, nearly 88 percent of North Carolina farms had poultry flocks, but they averaged just 22 birds each. Farms in the upper Midwest, by comparison, kept flocks that averaged 61 birds, earning the region the moniker of the nation's "egg basket." But several technological advances-such as artificially heated incubators, mechanical brooders, ventilated railroad freight cars, and mechanical refrigeration-set the stage for expanded poultry production.

During the first four decades of the twentieth century, women formed the vanguard of a quiet revolution in the poultry industry. They took advantage of increasing demand for eggs and fowl, experimented with new ways to raise and market chickens, and proved that poultry could turn profits. The state played a crucial role. Agricultural extension agents promoted poultry-raising innovations, and professors at North Carolina State College (modern-day North Carolina State University) conducted research on poultry feed, housing, and diseases. In the 1920s the state Department of Agriculture and commission merchants organized marketing cooperatives that shipped railroad car lots of eggs and live chickens to buyers in New York and other distant cities. At the same time, enthusiasm for poultry quickened when boll weevils invaded fields and profits from cotton and tobacco withered during the Great Depression. In 1929, for example, the 5.8 million chickens sold off of North Carolina farms brought in nearly $4.4 million, and the 240 million eggs sold reaped some $6.3 million.

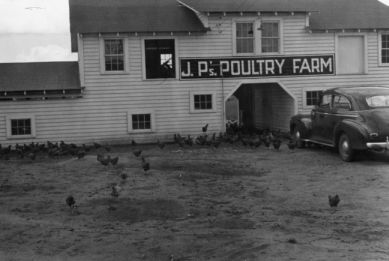

These economic lessons were not lost on farmers, especially those who lived in the foothills, where poultry growers started raising larger flocks in the 1920s and 1930s. Looking back on the development of the Wilkes County broiler industry, pioneer entrepreneur Charles O. Lovette credited much of its early inspiration to farm women who already understood the economics and care of poultry. Lovette himself got his start in the 1920s as a huckster who bought chickens, eggs, and vegetables from Wilkes County farms and country stores and then peddled the products in Charlotte and Winston-Salem. In 1942 Lovette's son Fred joined his father's huckstering business, and two years later he expanded the poultry buying and selling enterprise. In less than a decade, Fred had purchased a chicken processing plant, and what would become North Carolina's premier poultry agribusiness, Holly Farms, was born.

Fred Lovette entered the family business just as demand for eggs and chickens soared during World War II, as the federal government bought large quantities to serve in military mess halls. By 1943 North Carolina farmers had shattered all previous poultry records; growers, for example, sold 15.5 million chickens and grossed $15.7 million. Wartime demand accelerated the evolution of the industry and floated North Carolina and other southern states to the top of poultry production charts.

By the early 2000s, poultry was the largest food industry in North Carolina, with production of chickens, turkey, and eggs approaching $2.2 billion annually. Wilkes County led the way in broiler production, while Duplin County growers raised the most turkeys in the state. The nearly 3 billion eggs produced gave North Carolina a ranking of ninth in the nation. More than 4,300 farmers were involved in the poultry industry, employing more than 22,000 people in hatcheries, feed mills, and processing plants.

Increased production, however, exacted a toll. As poultry raising grew in scale and required more capital investment for houses the length of a football field and feed laden with growth stimulants and antibiotics, farm men usually assumed the position of managers, while women and children performed much of the actual work. As the industry underwent vertical integration, with companies such as Holly Farms controlling the operation from hatchery and feed mill to processing, agribusinesses closely supervised the operations of contractors, made key managerial decisions, and eventually reduced growers to little more than wage laborers. In 1991 a fatal fire at the Imperial Food Products plant in Hamlet demonstrated that workers who processed poultry often endured hazardous circumstances.

In their separate ways, contract growers and poultry factory workers have organized in efforts to improve these conditions. While consumers enjoyed an abundance of meat that was once reserved for Sunday dinner, many mourned the loss of the old-time taste of free-range chickens that factory farming destroyed. Changes in the poultry industry have created mixed blessings: consumers enjoy an abundant supply of inexpensive meat, but it is produced and processed under conditions that are open to criticism.