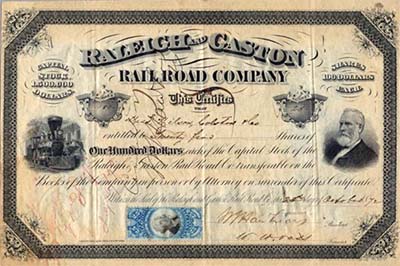

Throughout eastern North Carolina in the1840’s, the sound of a locomotive horn was heard, signifying the arrival of trains—and a new era of unprecedented prosperity. The promise of rail transportation, which was conceived and cultivated through the Experimental Railroad in 1835, led to the funding of North Carolina’s first self-propelled railroad, the Raleigh and Gaston line. Gaston in Halifax County was its northern terminus and Raleigh its southern end point.

Soon after the success of the Experimental Railroad, engineers in Virginia laid down track from Weldon, North Carolina, to Petersburg, Virginia. The line provided access to rails running along the east coast. Wake County residents and businessmen raised construction funds for a railroad in early 1836, with assurances from their counterparts in Petersburg (who would also benefit from the new rail) to contribute likewise. Enslaved people and their labor were leased to lay the rail on heavy wooden planks. Setbacks with financing and materials delayed the railroad’s completion until March 21, 1840. A week later, the Raleigh depot, at the corner of Salisbury and Halifax streets, received twenty bales of cotton from Petersburg, the line’s first commercial shipment on record.

The benefits of the Raleigh and Gaston line were apparent immediately. Soon after the line’s debut, local coaches began transporting goods to and from the main depot downtown. Other forms of transportation, such as steamboats and stagecoaches, would accommodate the trains’ arrival and departure times in their own schedules. The train allowed for quick transportation of goods, and also provided jobs for locals in Raleigh, as the Raleigh and Gaston line was widely known to “to give employment to native Southerners, in preference to reckless adventurers, either from the North or elsewhere.” Raleigh welcomed the promise of the iron horse with a three-day celebration heralded with cannons.

The Confederacy used the Raleigh and Gaston heavily towards the end of the Civil War, but years of contributing to the failed war effort took its toll on the Raleigh economy. In later years, other rails were laid, and in 1967, the Raleigh and Gaston line was incorporated into the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad. The Seaboard Office Building, constructed in 1861, today stands on Salisbury Street in Raleigh, having been relocated to that site in the 1970s from the junction of Salisbury and Halifax streets. The original site today is occupied by an underground parking deck.